It’s probably a safe bet to say that everybody knows that Android uses Java. However, the exact meaning of “uses Java” turns out to be quite complicated and nuanced. Therefore, in this post, I’ll describe how Android devices and various tools that we use for Android development leverage the Java platform.

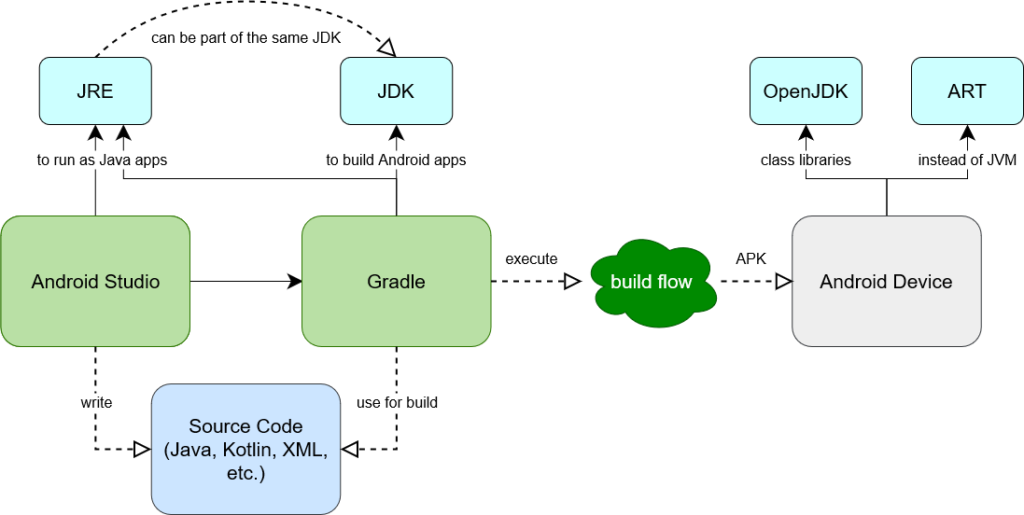

Let’s start with the conclusion – the following diagram shows the role of Java in Android ecosystem. If you get it right away, then great and you can stop reading this post. Otherwise, read on for more detailed explanations of each of the components that you see on this diagram.

Java Platform

Developers who write code in Java programming language usually call it just “Java”, so it’s natural to think of Java as just that: a programming language. However, as you might know, Java source code isn’t executable in its original form. First, you need to transform it into so-called bytecode and then use special tools to execute the bytecode on target devices. Therefore, the language itself is just one piece of a larger toolchain. That toolchain is called Java platform.

The most important parts of Java platform are so-called “JVM programming languages” (Java, Kotlin, Scala, etc.), JRE, JDK and JVM.

JRE

JRE stands for Java Runtime Environment. To understand what it does, imagine that you have a full-blown Java application and you want to run it. Since Java was designed with “write once, run anywhere” idea in mind, you should be able to run Java programs in many different environments. That’s really nice feature, but such flexibility comes with a cost: you can’t just run Java applications “natively”. Instead, you’ll need to install JRE on the target machine and then use this software to execute your Java application. In short: JRE is a set of tools needed to run Java programs.

Generally speaking, the main tools contained inside JRE are class libraries, class loader and JVM. I won’t elaborate more on class libraries and class loader (search the web if you’re curious what they do), but JVM is very prominent concept in Java world, so we need to discuss it as well.

JVM

JVM stands for Java Virtual Machine. This component executes Java bytecode and abstracts out (i.e. “hides”) the specifics of the hardware and the operating system installed on the host device. In some sense, you can think of JVM as an adapter between platform-independent Java bytecode and platform-specific hardware and software. In other words, JVM is the component which allows Java bytecode to be platform-agnostic.

JDK

Now you understand that you need JRE to run Java applications on host devices. However, to develop these applications, you’ll need special development tools to transform Java source code into executable bytecode classes, libraries and full-blown applications. Since most users will never develop applications, it doesn’t make sense to include these development tools into JRE. Enter Java Development Kit (JDK).

JDK is a software package that includes JRE and additional tools that can be used to develop Java applications.

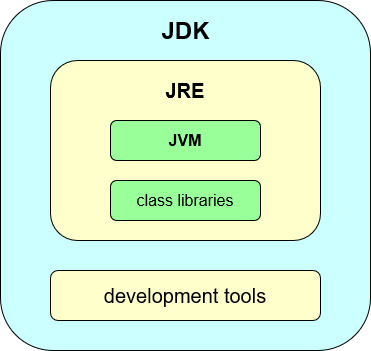

Schematically, the relationship between different components of Java platform can be described as follows:

Please note that the above diagram is very general and, in practice, all these entities are exceptionally complex pieces of software. Luckily, this complexity is abstracted away from application developers in most cases.

How Android Studio Uses Java

Android Studio is a customized version of JetBrains’ IntelliJ IDE, which is, in turn, a Java application. Therefore, as we established, to launch IntelliJ (and, consequently, Android Studio) on your computer, you need to have JRE installed. However, if you download and install Android Studio, you’ll be able to launch it even without JRE. How come?

Turns out that JetBrains folks decided to make the installation of IntelliJ simpler for their users, so they packaged an entire JRE with it. Therefore, when you install IntelliJ (or Android Studio), it will also install its own JRE. In IntelliJ, there is an option to change the default JRE to something else (action name: Choose Boot Java Runtime for the IDE), but Android Studio maintainers decided to get rid of it, so you’re stuck with the bundled option. In my opinion, that’s alright.

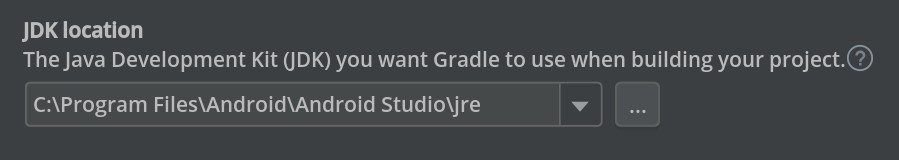

However, as we discussed, if you want to compile Java source code, you need JDK, not just JRE. Luckily, Android Studio takes care of that too. If I open Project Structure dialog and go to SDK Location tab, I see this drop-down at the bottom:

Just like with JRE, Android Studio comes bundled with its own JDK and uses it by default. For some reason, the directory is called “jre”, but don’t worry – it contains an entire JDK and its name is not important.

Note, however, that the caption of the aforementioned drop-down says that the selected JDK will be used by Gradle, not Android Studio. So, let’s talk about Gradle.

How Gradle Uses Java

Gradle is a build tool. It takes a piece of source code as input and then executes a “build” flow which transform that source code into something else. During the build flow, Gradle will usually use additional third-party tools because it doesn’t know how to deal with the source code on its own. In some sense, you can think of Gradle as an orchestrator of the build process: it doesn’t do the work by itself, but it knows about all the steps in the flow and it also knows who is responsible for executing each of these steps.

In the context of Android development, Gradle’s main role is to transform the source code and the associated resources into APK and AAR archives for applications and libraries respectively.

Fundamentally, Gradle is also a Java application, so you need to have JRE installed to run it. However, when you use Gradle to build source code written in JVM languages (Java, Kotlin, Scala, etc.), JRE won’t suffice and Gradle will need a full JDK. That’s why you have to specify JDK location for Gradle inside Android Studio.

As we have already discussed in the previous section, Android Studio comes with its own JDK which it uses by default. Therefore, in practice, you won’t need to install your own JDK to execute build flows from within Android Studio (unless you have a special reason to change the default).

Android Gradle Plugin

Since I’ve already mentioned Gradle, let’s discuss Android Gradle Plugin (AGP) as well.

First, consider this description from the official Gradle docs:

Gradle at its core intentionally provides very little for real world automation. All of the useful features, like the ability to compile Java code, are added by plugins. Plugins add new tasks (e.g.

JavaCompile), domain objects (e.g.SourceSet), conventions (e.g. Java source is located atsrc/main/java) as well as extending core objects and objects from other plugins.

In other words, Gradle provides just high-level scaffold for automation and assumes that build flows for specific targets will be implemented by plugins. Some plugins are maintained by Gradle team while others come from third-party developers.

AGP is a Gradle plugin for Android development. It is maintained by Google and its release cadence is kind-of-synchronized with releases of Android Studio. In addition, as a general rule, newer versions of AGP aren’t backward-compatible with older versions of Gradle (i.e if you want to migrate to newer AGP, you might also need to migrate to newer Gradle).

All in all, AGP is a plugin developed by Google which makes it possible to build Android apps using Gradle.

Executing Gradle Builds from a Command Line

In some cases, you might want to execute Gradle builds from a command line rather than from Android Studio. To accomplish this task, you’ll need to invoke gradlew.bat (Windows) or gradlew (Mac and Linux) scripts.

For example, if you’re on Mac and want to build a debug version of your application, you can use the following command (assuming you don’t have any flavors):

./gradlew assembleDebug

Now, remember the JDK location setting inside Android Studio that we discussed earlier? If you build from a command line, it has no effect. In fact, you don’t even need to have Android Studio installed to execute Gradle builds from a command line. This is great for e.g. building artifacts on a continuous integration server, but it also means that now you’re responsible for telling Gradle where it can find the JDK.

There is a widespread convention to define an environment variable called JAVA_HOME and set its value to the location of JDK installation directory on your machine. Luckily, Gradle is aware of this convention. Therefore, to invoke Gradle builds from a command line, you just need to set JAVA_HOME correctly and Gradle will pick it up. If you build from both Android Studio and a command line on a specific machine, it’s recommended to make sure that JDK location setting inside Android Studio and JAVA_HOME point to the same place. This way, you’ll use the same JDK irrespective of where you initiate the build from.

How Android Devices Use Java

Interestingly, despite the fact that we use JVM programming languages to write Android apps, there is actually no Java platform running on Android devices. Not formally, at least. To understand this aspect, we’ll need to go back in history to the roots of Android platform.

When Google had developed Android, they decided to base it on Java platform. However, due to legal considerations, instead of adopting “proper Java”, Google decided to basically fork Java platform and modify it according to their needs. As a result of this approach, there is no JVM on Android devices. Instead, Google had used so-called Dalvik Virtual Machine (DVM), which was later replaced by Android Runtime (ART).

In addition to using a different virtual machine, Google re-implemented many standard Java APIs inside Android to allow developers to use these familiar constructs when writing Android applications (e.g. java.lang.*, java.util.*, etc.). Later, in Android 7, Google decided to incorporate OpenJDK into Android and replace custom re-implementation of Java APIs with OpenJDK’s versions. However, there is still no JVM in Android.

The bottom line is that, formally, there is no Java platform inside Android devices. There are just some parts of Java that Google decided to use, accompanied by many custom modifications and additions.

Summary

So, at a very high level, that’s the interplay between Android, Android Studio, Gradle and Java.

If you notice any inaccuracy or missing information, or just have a question, please let me know in the comments section below.

Great job explaining the interconnection of those entities, thank you very much for sharing Vasiliy 🙂

As always a mind blowing explanation of how Android Studio, Java, JVM, JDK, JRE and gradle interplay to make android developers life awesome. Sometime we keep using the tools without knowing how’s and why’s. This blog cleared some cloud.

Thanks for the article Vasiliy. This is very useful and important information that many developers are unfortunately not 100% familiar with.

Now Google have won the long running court case with Oracle, do you think they’ll upgrade from java 8 to newer versions? I hope so as there’s very little I like about Kotkin.

Hi Peter,

That’s a very interesting question which I can’t even speculate about from the top of my head. I’ll surely write a blog post about this lawsuit and the implications of Google’s win, so you’ll be notified if you’re subscribed 😉

Why does an Android device need the entire OpenJDK? Shouldn’t it be able to work with just JRE?

Yes, you’re right, Android devices don’t need the entire OpenJDK. In fact, they don’t even need the entire JRE (e.g. they don’t need the JVM). Ultimately, OpenJDK re-implements the JDK, but you can (and Android devives do) use just parts of it. However, since OpenJDK is the name of the project, not a designation of a functionality, once you use any sub-part of OpenJDK, you’ll say that you use OpenJDK. So, Android devices don’t have an entire JDK on them, but they do incorporate parts of OpenJDK.

Hope this clarifies the terminology a bit.

Hi Vasiliy! Thank you for posting this great thought. Is it okay for you to translate this article into Korean for my blog? I’m sure it will give a lot of insight to other developers.

Hi Sana,

You have my permission to translate to Korean and publish on your blog. Good luck.